The creative experiment begun by the Parisian expatriates, the modernists of the pre-war generation of Gertrude Stein and Sherwood Anderson, was continued by the young novelists and poets who came to American literature in the 1920s and brought it worldwide fame. Their names throughout the twentieth century were firmly associated in the minds of foreign readers with the idea of U.S. literature as a whole. They were Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Francis Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos, Thornton Wilder, and others, mostly modernist writers.

At the same time, modernism in the American turn differs from European modernism in its more obvious involvement in the social and political events of the era: the shocking war experience of most authors could not be silenced or circumvented; it required artistic embodiment. This invariably misled Soviet researchers, who declared these writers to be “critical realists. American criticism labeled them the “lost generation.

The very definition of the “lost generation” was casually dropped by Stein in a conversation with her chauffeur. She said: “All of you are the lost generation, all the young people who have been to war. You have no respect for anything. All of you will go to sleep. This saying was accidentally heard by E. Hemingway and used by him. He made “All of you are a lost generation” one of the two epigraphs to his first novel, And the Sun Rises (Fiesta, 1926). Over time, this definition, precise and succinct, acquired the status of a literary term.

What are the origins of the “lostness” of an entire generation? The First World War was a trial for all mankind. One can imagine what it became for the boys, full of optimism, hope, and patriotic illusions. In addition to the fact that they directly fell into the “meat grinder”, as they called this war, their biography began immediately with a climax, with the maximum overstrain of mental and physical strength, with the hardest test, for which they were completely unprepared. Of course, it was a breaking point. The war forever knocked them out of their usual patterns, defined the structure of their world outlook – acutely tragic. The beginning of the poem Ash Wednesday (1930) by the expatriate Thomas Stearns Eliot (1888-1965) is a vivid illustration of this.

Other program poems of the “lost generation” – T. Eliot’s poems “Barren Land” (1922) and “Hollow Men” (1925) are characterized by the same sense of desolation and hopelessness and the same stylistic virtuosity.

However, Gertrude Stein, who claimed that the “lost” had no respect for “anything,” proved too categorical in her judgments. Not only did their age-long experience of suffering, death and overcoming make this generation very resistant (none of the writing brethren “drank,” as they had predicted), but also taught them to unmistakably distinguish and honor the lasting values of life: communion with nature, love of women, male friendship and creativity.

The writers of the “lost generation” never formed any literary group or had no single theoretical platform, but their common fates and experiences shaped their similar attitudes: disillusionment with social ideals, search for enduring values, stoic individualism. These factors, along with a shared dramatically tragic worldview, determine the presence of a number of common features in the prose of the “lost”, evident despite the variety of individual artistic handwriting of the authors.

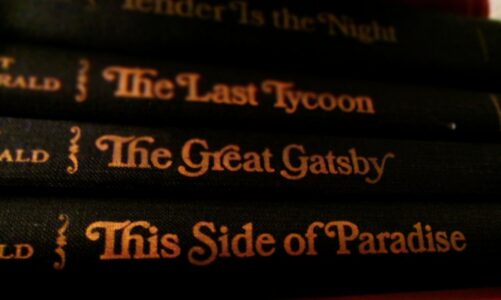

Commonality is manifested in everything from the subject matter to the form of their works. The main themes of writers of this generation – the war, the front-line everyday life (“Farewell to Arms” (1929) Hemingway, “Three Soldiers” (1921) Dos Passos, a collection of stories “These thirteen” (1926) Faulkner, etc.), and the postwar reality. ) and postwar reality-the “Jazz Age” (Hemingway’s And the Sun Rises (1926), Faulkner’s Soldier’s Reward (1926) and Mosquitoes (1927), the novels The Beautiful but Doomed (1922) and The Great Gatsby (1925), the short story collections The Jazz Age Stories (1922) and All the Sad Young Men (1926) by Scott Fitzgerald).

The two themes in the work of the “lost” are interrelated, and the connection is causal. The “war” works show the origins of the lost generation: the frontline episodes are presented by all authors harshly and unvarnished – contrary to the tendency to romanticize the First World War in official literature. The works on “peace after the war” show the aftermath – the convulsive merriment of the “jazz age”, which reminds us of dancing on the edge of a precipice or feasting during the plague. It is a world of war-torn fates and fractured human relationships.