World War II gave a new direction to literary development in the United States. “Anything not connected with the war must be postponed,” was the chief unwritten law of the wartime era.

Moreover, the war drastically reduced the productivity of all writers. As W. Faulkner remarked, “you don’t write well in war.” Many writers were at the front as war correspondents (like E. Hemingway) or in the active army (like J. Cheever, S. Bellow, N. Mailer, C. Vonnegut), and they naturally had no time for artistic creativity. Most importantly, however, both they and those who remained in America needed first to comprehend this newly changed world and the place that man occupied in it. Genocide and the possibility of total nuclear annihilation affected not only European Jews and Japanese, but all people on both sides of the globe, destroying the last vestiges of national American naivety and “innocence.

The end of the previous period of U.S. literary development was vividly underscored by the deaths of several major writers of the 20s and 30s: Scott Fitzgerald and Nathaniel West were gone in 1940, S. Anderson passed away in 1941, and G. Stein in 1946. The era of modernism is gone, although its greatest representatives – E. Hemingway and W. Faulkner – still continued to create.

With the end of the war in the national literature came a new generation of young writers with honest realistic works about their tragic experience. The writers who first gave a reflection of World War II in American prose were J. Hersey (Hiroshima, 1946), N. Mailer (Naked and Dead, 1948), I. Shaw (The Young Lions, 1948), G. Wook (The Caine Conspiracy, 1951), J. Jones (From Here and Forever, 1951) and other “war novelists”, as critics defined them. M. Cowley lamented at the time that, unlike the First World War, which produced a vivid literary experiment, the Second brought to life only the most traditional realism. Very soon, however, it became clear that Cowley had been somewhat hasty in his judgments.

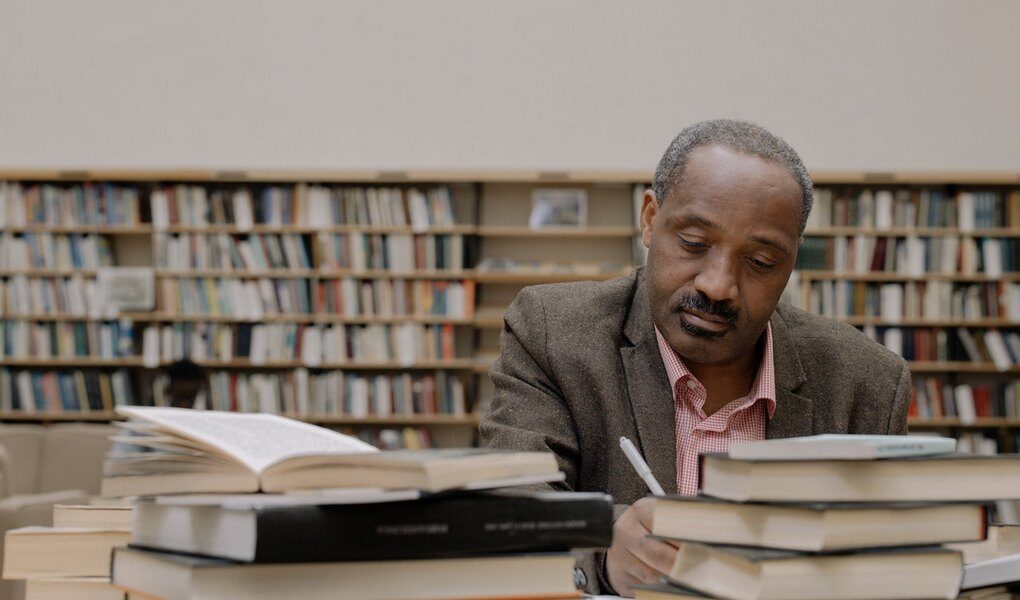

After World War II, Jewish-American literature came into the national spotlight. Its authors spoke as if they were speaking on behalf of millions of European Jews who were victims of genocide to whom they owed a debt of blood. They had yet to make sense of this monstrous historical experience. It is telling that the most impressive works about the genocide did not come out until the 1970s: Singer’s Shosha, Epstein’s The King of the Jews, Bellow’s Mr. Samler’s Planet. In the meantime, it was necessary to rethink the unique experience of American Jewry.

Since the mid-1940s there has been an incredible flowering of Jewish-American literature – poetry, drama and, especially, prose. It is at this time that the work of J.B. Singer becomes a fact of American literature, the World War I-born S. Bellow, A. Miller, and later B. Malamud and writers of the next generation (born in the 20s and 30s): Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, Herbert Gold, Joseph Heller, Edgar Lawrence Doctorow, Grace Paley, Leslie Epstein and many others begin to publish. Most are postmodern writers.

Postwar Jewish-American literature is distinguished from earlier literature by a special sense of history, heightened by the tragic experience of Jewishness. Associated with the sense of historical instability is the desire of the postwar generation of Jewish-American writers not only for religious, political, or ethnic self-definition, but above all for existential self-definition: “What does it mean to be human?”

Not surprisingly, the most striking and yet very diverse works in U.S. literature about World War II, a time that devalued the human person to the utmost, were written by Jewish-American writers. Norman Mailer’s novel The Naked and the Dead (1948), for example, stunned readers with the poignant authenticity of direct war testimony. “Joseph Heller’s Amendment-22 (1961) presented the war and everyday life of the “heroic” American army as utterly absurd, eliciting Homeric laughter and bitter doubts about the sanity of the world order as a whole.

Isaac Bashevis Singer’s (1904-1991) novel Shosha (1978), which shook America as a reflection on the catastrophic madness of genocide, was also a book about the tragedy of modern man, whose mystery of existence is dark to him, because the path of salvation he seeks, he is essentially searching blindly. The author sees the only answer to the nonsense of historical catastrophe in the fatal loyalty of man to his human destiny. This fidelity is embodied by Singer in the image of the blessed “foolish girl” Shosha.